Tylko dla subskrybentów więc wklejam.

Special to Subscribers: Niall Stokes introduces 'North Side Story'.

24 January 2014

"We'll make our own rules."

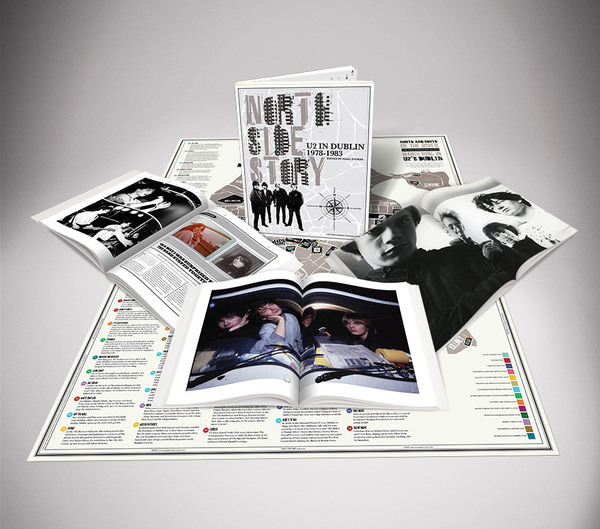

Following our interview with Hot Press Editor Niall Stokes about North Side Story, here's some edited highlights of his introduction to the book... which (if you've subscribed for 2014) should be landing in your mailbox any day now. (Not signed up for another year with U2.com ? Resubscribe here for $40 and we'll send you this limited edition publication.)

NORTH SIDE STORY - PART 1

Derek Rowen, a painter and sculptor by trade, is one of the most successful artists of the modern generation in Ireland. He grew up on Cedarwood Road in Ballymun, on the North side of Dublin, where he lived throughout the 1960s and into the '70s. One of his neighbours and close friends was Paul Hewson.

As teenagers, the two youngsters painted together in the garage of Paul's house, relishing that first taste of the pleasures of self-expression. Later, when the punk era dawned, they also became part of a local posse who hung out together and who - by way of social glue - formed an imaginary world, which they called Lypton Village. In this parallel universe, with its echoes of Lord Of The Flies, they adopted distinctive new identities: Derek was renamed Guggi; Paul was given the name Bono; another friend, David Evans, was rechristened The Edge; and Fionán Martin Hanvey became Gavin Friday. It was as if, towards the end of what in many ways had been a cruel decade, they were desperate to disassociate themselves from everything they knew about Irish society: the compromises of their parents' generation, the violence that was raging in Northern Ireland, and the conventional, low expectations in relation to work and careers that likely lay just around the corner unless they found a different way.

As the impact of punk rock spread into Ireland, Bono and Guggi got involved in separate bands. Bono joined an outfit which started as Feedback, briefly became The Hype and finally settled as U2. Derek linked up with Gavin Friday in The Virgin Prunes. But he and Bono remained close friends, hanging out together and occasionally sharing the stage at gigs. Guggi even stood in for the young U2 drummer Larry Mullen, when he couldn't attend a photo session that had been organised for the band.

Looking back at that time in Ireland, Guggi says now that he remembers everything in black and white. It was as if Ireland was still stuck in a 1950s time-warp - which in many ways it was. And yet, all was not irredeemably bleak. While the atmosphere of stagnation was profound for boys growing into, and becoming, young men, underneath all that, currents of far-reaching change were swirling. Gradually clawing their way out of the anonymity of their Northside suburban upbringing, U2 and their cohorts would in many respects come to embody what that change was all about...

From the 1960s on, more children than ever before were being born in Ireland. There was an explosion in the youth population. More houses were needed. The capital city, Dublin, began to sprawl. Planning in Ireland had always been haphazard at best. Shops, parks and other amenities may have been written into the plans for the new suburban estates that were spreading out to the North, South and West of the city, but unscrupulous builders frequently got the houses up and moved shadily on, turning many of the new areas into what, as Gavin Friday observes, felt like endless wastelands of identical housing, populated by hordes of restless youth. And in those wastelands, violence was never far from the surface.

Over the years, attempts to clean up the inner city had seen people being moved from the run-down urban tenements to new estates on the outskirts of town, beginning in the 1950s and continuing into the '60s, when the now infamous seven towers of Ballymun were built. Further out, more affluent neighborhoods were constructed during the '60s and into the '70s, including better quality enclaves in places like Portmarnock, Malahide and Bayside in Sutton. Gradually, the city was spreading all the way out to Howth on the North side and Dun Laoghaire on the South. This was where the new music would come from.

Bob Geldof and The Boomtown Rats, the first Irish band to capitalise on the upsurge of punk, were based on the South side. Something's coming, you might have said. And indeed it was. There was a need for a band that would tell the North Side Story. Even as the Rats were boarding the plane to leave, an even bigger phenomenon, its hour come at last, was slouching towards Sutton to be born...

NORTH SIDE STORY - PART 2

As the 1970s wore on, there was still a very high level of emigration among 18 to 25 year olds, with thousands waving goodbye to Ireland never to return. And rock musicians, in particular, seemed to believe that to have any hope of making it internationally, you had to get out of here. Through the 1960s, Van Morrison, Rory Gallagher and Thin Lizzy had all gone. Horslips, who released their debut album in 1972, were the exception, choosing to base themselves in Ireland throughout the decade of their success: their stance was emblematic of a difference in attitude that was becoming more and more evident among the new generation that was pushing through, often against the odds, in the arts and in music, which could be expressed in a simple credo: "We'll make our own rules."

Now and then, events take on a momentum of their own: this was one of those moments. Ireland was on the cusp of an extraordinary convulsion, which would see the influence of the once all-powerful Catholic Church being permanently curtailed. Afterwards, nothing would ever be the same again.

It's hard to spot the influences when you are in the middle of them. For a start, the launch of RTÉ television at the beginning of the 1960s led inevitably to a far greater number of people being exposed to British television programmes and to the less pious, more liberal ethos that prevailed generally in the UK.

Largely through television, too, Irish people had been made aware of the emergence of the counter-culture, of the more widespread use - for better or worse - of psychotropic drugs, of student protests, of opposition to the war in Vietnam and of the challenges to authority which, in all sorts of diverse ways, were being voiced through rock music.

Similarly, by the 1970s, the Women's Movement, which had become such an important force internationally, was finally gaining traction in Ireland: for the first time, all the tired old assumptions about male supremacy were being exposed. Liberal voices on sex and sexuality were finding a platform through the work of the Irish Family Planning Association. And in places like the Project Arts Centre, a less conventional breed of artists and activists - painters, poets, playwrights, actors and musicians - had gathered in a spirit of experimentation and adventure. The culture of silence and looking the other way which had dominated in Ireland since the inception of the State, was under pressure like never before. The old authoritarianism was no longer acceptable...

As the 1970s ground on, the explosion of the punk scene in the US first and then the UK triggered an acceleration in the pace of change here. Hot Press arrived on the scene in 1977, and quickly established a reputation for iconoclasm. We had a photo of the outgoing Irish cabinet, with Taoiseach (the Irish Prime Minister) Liam Cosgrave to the fore, on the front cover of our launch issue, surrounded provocatively by a cast of rock 'n' roll reprobates, including Rory Gallagher, Keith Richards, Bob Marley, Bob Geldof and Patti Smith, among many more. The summer of ‘77 was a watershed for music in Ireland. Rory Gallagher played the first Macroom Festival in June and among those in attendance was David Evans, who read his first copy of Hot Press there. In August, Thin Lizzy topped the bill at a festival in Dalymount Park, that also included Irish new wave outfits The Boomtown Rats and The Radiators (both returning from the UK for the show) in the lineup, as well as Graham Parker and The Rumour. Bono, Gavin Friday and Guggi attended the gig. The feeling that Ireland was finally coming of age in rock 'n' roll terms was irresistible.

Over the months that followed, Hot Press became a rallying point for political dissenters and musical visionaries alike. Among those who wrote for us in the early days were Bill Graham, who first brought U2 to the attention of the world, Máirín Sheehy, Dermot Stokes, Liam Mackey, Declan Lynch, Karl Tsigdinos, John McKenna and Dave Fanning, as well as writers who had been involved in the formation of the Irish Writers' Co-op, like Neil Jordan, Desmond Hogan and Jim Sheridan. Neil McCormick joined the staff shortly afterwards. Tara Winter, Barry McIlheney, Peter Owens, George Byrne, Jackie Hayden, Graham Linehan, Arthur Mathews, Nick Kelly, Fiona Looney and Damien Corless would all come through the ranks. Colm Henry started taking pictures.

During 1977, we covered early Irish gigs by The Clash, The Stranglers, The Ramones and The Jam. We interviewed The Sex Pistols, The Damned, Patti Smith and Television. But we also had Van and Rory and Philo on the cover, making the link across the rock 'n' roll generations, in a way that the more fad and fashion conscious UK music press often struggled to. Equally, we celebrated the DIY spirit of punk and helped to give it legs here. Suddenly the shibboleths imposed by the ageing, Church-approved, artistic old-guard had lost all of their power to control: under the new dispensation, like Lou Reed, David Bowie or Iggy Pop, you did creatively what the fuck you wanted.

The initial response of the new wave of Irish punk bands was still to cut and run. The Boomtown Rats were first to go, having signed a big deal with Ensign Records, a subsidiary of Phonogram (now Universal). Even as he headed for the airport, lead singer Bob Geldof was shouting the kind of imprecations that would culminate in the vicious put-down of ‘Banana Republic', a couple of years later. It was a song in which he lampooned the image of Ireland as the land of saints and scholars, branding it instead a ‘septic isle'. The Radiators From Space were next up, with Philip Chevron declaring bitterly in their debut single ‘Television Screen', released in 1977: "I'm gonna put my Telecaster through the television screen/ ‘Cos I don't like what's going down..." They too headed for London, where Chevron completed the powerful ‘Song of the Faithful Departed' for the Ghostown album. "This graveyard hides a million secrets," he sang about Dublin. "And the trees know more than they can tell/ The ghosts of the saints and the scholars will haunt you/ In heaven and in hell."

Up north, The Undertones from Derry and Stiff Little Fingers from Belfast both hightailed it to London as well. It seemed like this was what you had to do. But in truth there was another way...

NORTH SIDE STORY - PART 3

I remember, on a cold autumn afternoon, sometime early in the 1970s, retreating to the back garden of the three bedroomed house in Rathfarnham, on the South side of the city, that our family of ten occupied. Out the back was a vacant field in which cattle occasionally grazed. To either side were houses the same as ours, strung endlessly this way and that. Looked at coldly, it was the proverbial Dead End Street about which Ray Davies had written. And yet I saw and felt something transcendent in the simple fact of just being there. This was the reality I had grown up with. It was what I knew. And I thought: someone has to write the story of this thoroughly unremarkable place, the story of the suburbs of Dublin and the confused and conflicting emotions experienced by young men and women growing into, or striving to grow into, adulthood here. I felt strangely empowered, caught up in a moment that was suddenly ripe with as yet unarticulated possibilities.

As it turned out I was not alone in that feeling.

All over the city voices were rising. It was a little bit later, in the spring of 1978, that U2 began to make their presence felt. Even then it seemed premature: some of the band were still at school and so there was a period during which they were forced into a holding pattern, before they could really commit to it collectively. But once they did, there was no stopping them.

In some ways they were fortunate, to have landed at a time when all bets were truly off. Punk rock empowered people, here as well as in Britain, in a way that 1970s pub rock never could have. It didn't matter whether you were able to play guitar or not, you could get up on stage and perform. You could spike your hair, stick safety pins through your nose and slather on the make-up if that was what turned you on. You could divest yourself of your past, change your name and take on a different identity. Nothing was sacred anymore. But those new freedoms were not enough in themselves. It was what you did with them than counted. That was where Hot Press came in. That was where the Project Arts Centre came in. That was where Steve Averill, Bill Graham, Paul McGuinness, Jackie Hayden, Ian Wilson, Mannix Flynn, Jim Sheridan and others who were getting up off their arses and agitating to create the space in which new music, new art and new thinking could flourish, all came in.

In a sense, that is what this book is about: it is the story, as told in Hot Press at the time, of four young men from the suburbs on the North side of Dublin - Adam, David, Larry and Paul - who seized the day, rose above the barriers on which so many of their contemporaries became snagged, reimagined their own world individually and collectively and started to make a noise that would ultimately capture the hearts and minds of millions of people all over the planet. And it is about the city which provided the backdrop for that remarkable uprising.

To deepen our understanding of the story, we have added a number of pieces written about the band, in those early days, in the UK, Holland, Belgium, Germany and Sweden. And we have also spoken to many of the key participants in the rise of the young U2. What emerges is an extraordinary, and hugely fascinating, Portrait Of The Artists As Young Men.

Looking at it now, though, and listening to the fresh testimony of their friends and colleagues from the early days, many of whom are speaking about U2 publicly for the first time, something else emerges about the band and their place in Irish history.

Following the War of Independence in Ireland, which ended in 1922, two separate and essentially sectarian States, south and north of the border, were founded on the island of Ireland. The sectarianism and isolationism which gripped the country for the next 50 years had a shockingly negative, repressive effect. Held in place as it was by authoritarianism of one kind or another, that sectarianism could sustain itself for just so long - and it did. But there were too many conflicting forces at work for it to last beyond that moment when modern communications opened us up to the world - and the world up to us. The past was another country. And it was doomed.

In many ways, the personnel who - almost by accident - clustered to form U2, themselves reflected the inevitability of change. In 1978, what did it mean to be Irish? That was a more open question than ever before and the members of U2 were primed to know that better than most. Adam Clayton had been born in England of English parents and moved to Dublin at the age of five. David Evans was born in England of Welsh parents and moved here at the age of one. Though they might not have made a big deal of it, the background of both families was Protestant. Born in Ireland of Irish parents, Paul Hewson was the son of a Catholic father and a Protestant mother. Larry Mullen's parents were both Irish and Catholic.

U2, in other words, were as close as you could get at the time, in an Ireland that was monocultural to an extraordinary degree, to a licorice all-sorts of nationalities and faiths. They attended Ireland's first interdenominational school, Mount Temple Comprehensive. And they discovered their true identity, finally, in the shamanistic rituals of rock ‘n' roll. They were Irish. But they were much more than that too...

The memories gathered throughout the following pages, from those who knew them in the early days, are revelatory. Almost everyone agrees that Bono in particular was convinced from the outset that U2 could become the biggest band in the world. He was not wrong.

History shows that these four young men from the North side of Dublin struck a chord, captured the zeitgeist, created a unique sound and went on to make some of the richest and most resonant records in the annals of rock music. And they proved themselves, again and again, through a series of tours of ever escalating ambition, as one of the consummate live acts.

But how and why did it all come about? What drove Adam, Bono, Edge and Larry? And how come they are still together after all these years? That's what we are here to explore in North Side Story. Now, let's take it from the top.

One, two - one, two, three, four!